One of the most overlooked areas of tax savings is understanding how realized gains and losses impact your taxes. When you sell an investment, calculating cost basis and good record keeping plays a vital role in controlling those savings now and in the future.

To confuse things the IRS made several cost basis reporting changes. It revamped stock basis reporting in 2011, followed by changes in mutual fund, ETF, and DRIPs (Dividend Reinvestment Plans) in 2012.

Some say it makes the process easier. Which it does. Really, it enforces accuracy so nobody fudges their numbers. Good or bad, the changes force you to make cost basis accounting decisions at the time of sale. This is easy enough when you sell all the shares of stock.

But it doesn’t always work out that way. Maybe you want to sell half your shares. Maybe there are reinvested dividends to account for now and the intricacies of mutual fund shares, reinvested distributions, and return of capital. Or you just want to rebalance your portfolio. In other words, it’s complicated.

How you report cost basis directly affects your tax bill, which is the point of this guide. It’s also a big piece of a tax-efficient investment strategy. That is where you can save money by knowing the rules and planning ahead for taxes.

When we talk investments (stocks, ETFs, mutual funds, etc.), the basis is the cost at the time of purchase plus any transaction costs or commissions. There are exceptions like gifts and inheritance, which we’ll cover later.

When you buy 1,000 shares of Ford at $14 and your broker charges you a $10 commission, your cost basis is $14,010 for those shares. That transaction is given a unique tax lot ID so you and the IRS can track those shares separately from other Ford stock you might buy later.

The process is the same for mutual funds, ETFs, and reinvested dividends.

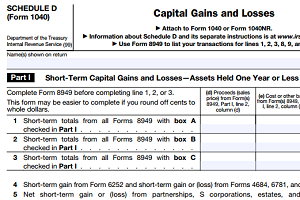

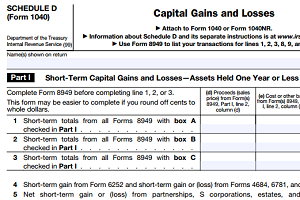

Anytime you sell shares for a profit, it’s known as a capital gain. The IRS has two classifications of capital gains:

This is important. The tax rate for each capital gain is different and there are rules on how each gain is offset by a capital loss.

Anytime you sell shares for a loss, it’s known as a capital loss. Again, the IRS has two classifications of capital losses:

A capital loss offsets a capital gain or your income which lowers your tax burden. The IRS has rules in place on what gets first priority.

The rule of thumb is – capital losses first offset gains of the same type, then gains of the other type, and lastly, your income.

So, if you have a big short-term capital loss, it will first offset any short-term gains. Anything left, will offset any long-term capital gains. The rest will offset other income up to $3,000 per year. Any loss beyond that is rolled forward to future years.

When a loss exceeds the $3,000 deduction limit, it can be carried over to future tax years. The same rule of thumb applies to carryover losses. It offsets capital gains first, then income, and the rest is carried forward for the next tax year, and so on until there is no loss left.

Say you sell several stocks for a net $4,000 capital loss this year. You can write off $3,000 of that loss against your income for the current tax year. Then you can use the remaining $1,000 loss to offset any capital gains or income next year.

None of this matters if you use the wrong cost basis method. Do you remember the lot ID mentioned earlier? When you sell shares, you need to decide which lot ID those shares correspond too. If, like in the Ford example earlier, you only bought 1,000 shares of Ford, there is only one lot ID to choose.

But what if you bought 1,000 shares of Ford, three separate times, each at a different share price. Now choosing a lot ID is important. To do this, you’ll need to specify one of these cost basis methods at the time of sale:

Every broker and fund company sets a default basis method. If you’re not sure which one is used, contact your broker and find out. Their default method makes tracking your gains and losses easier for them. It is not set up to give you the best after-tax returns.

When you sell all the shares of a stock, you have the full capital gain or loss. But when you only sell some of your shares, you can pick those with the basis and holding period that gives you the best tax results.

By the way, there isn’t a right cost basis method per se. It all depends on your existing capital gain/loss, how a lot ID sale changes that capital gain/loss, the potential for future capital gain/loss on remaining unsold shares, and your tax rate.

I always use the specific lot method because it offers flexibility. In the end, you need to weigh the trade-off between your current tax bill and possible future taxes.

To do this, you’ll need to keep track of everything. Now, I know that brokers and fund companies do it for you. It’s always a good idea to have your own records. So, to get you started, I included a free cost basis spreadsheet template at the bottom of this post. Plus, if you ever switch brokers, inherit stock or fund shares, or just need to double-check, you’ll have the records.

You calculate the cost basis for a stock you’ve purchased by taking the cost of the shares plus the commission your broker charges. Let’s use the Ford example from earlier: 1,000 shares at $14/share with a $10 commission. Your cost basis is $14,010, per share it’s $14.01.

What if you sell those 1,000 shares of Ford for $12? Your broker charges another $10 commission for the sale and your proceeds are $11,990. Don’t forget to subtract the commission from the sale. You get a capital loss of $2,020 ($14,010 cost basis – $11,990 sale).

If a company declares a stock split, the cost basis of your old shares is evenly split between the old and new shares. Say, you own 1,000 shares with a cost basis of $20/share ($20,000 basis). The company does a two for one stock split. Now, that $20,000 basis is split between 2,000 shares with a $10/share basis.

When calculating the cost basis for ETFs, just use the same process we went through for stocks. Thanks to the low costs of ETFs, it’s easy to see someone owning the same ETF for years, regularly buying new shares each month and reinvesting dividends. Not unlike a mutual fund.

Every one of those events is a new tax lot ID to track with a different holding period and basis. When you do that over several years it’s important to keep accurate records for tax purposes.

The basis calculation for reinvested dividends is the same as those used for ETFs and stocks but is easily overlooked with DRIPs. Dividend Reinvestment Plans automatically buy shares when dividends are paid out. It’s no different from having the dividends paid in cash, then you immediately turn around and buy new shares. So you get a new lot ID for each reinvestment.

Over several years, the number of shares can quickly add up. So will the number of lot IDs to choose from when you finally start selling shares. This is why tracking everything is important.

Mutual funds have been very popular over the past two decades. They usually come in two forms: load and no-load mutual funds.

You calculate the cost basis for mutual funds the same as stocks: purchase price plus transaction cost or commission. The purchase price will be the net asset value (NAV) on the day shares were purchased.

A mutual fund with a 5% load, would have a cost basis of NAV plus a 5% commission. So 100 shares bought at an NAV of $10/share ($1,000 + 5%($1,000)) would have a $1,050 cost basis with a basis of $10.50/share.

The average cost method is one method allowed by the IRS when you sell mutual fund shares. You figure out the average cost by adding up all the money invested into the fund, including reinvested dividends, and divide by the number of shares you own. Then you assume the sold shares are a long-term capital gain/loss.

It’s the easiest method to use for long-held funds, but it probably won’t offer the best tax savings. Once you choose the average cost method, the rest of the shares in that fund must use it too. It’s worth weighing before you lock shares into the average cost method.

When you inherit stock your cost basis is calculated based on the date of the previous owner’s death. Even if the previous owner bought those shares years or decades ago at a lower cost basis, you won’t get hit by the tax burden. Instead, your cost basis is updated to the current valuation.

For stock, your cost basis per share is the share price on the date of death. It’s the same for ETFs, mutual funds, and any asset where basis plays a role in taxes.

The one exception is if the estate of the previous owner was subject to estate tax. In that case, an alternative valuation date six months after the previous owner’s death can be used by the executor to value the shares. The executor decides on the date used to calculate basis.

Unfortunately, gifts don’t get the same privileges as an inheritance. When a family or friend is generous enough to gift you shares of a stock or fund, your basis stays the same as when it was purchased.

There is one exception. When you sell those shares for a loss, the basis is the lesser of — the previous owner’s basis or the value when you received the shares. You can’t benefit from the previous owner’s cost basis.

If you do receive shares as a gift, make sure you find out all the cost basis information from the previous owner and the value on the day you received them.

When you inherit or receive stock as a gift, the last thing anyone thinks about is the original cost basis. Or maybe it was overlooked when you switched brokers years ago. Either way, its information you’ll need when you sell the stock.

When dealing with stocks, this process gets difficult the further back you go. Capital changes, things like spinoffs, stock splits, or issued dividend shares, become more likely. It can make a big difference on the original cost basis.

This can be difficult if you don’t know the date it was bought. In which case, you can ask the prior owner or their old broker for past transaction statements.

But if you do know the date, you can use historical stock quotes to find the information. Just take the average of the high and low price on the date in question. Yahoo Finance is a good place to start and adjusts all historical prices for stock dividends and splits.

You might run into a few special situations where you have to adjust basis. Return of capital is the most common found. I’ve covered it with REIT tax rules, but you see it with mutual funds and MLPs too.

When a fund, REIT, or MLP sells an asset, it can reinvest the money or pay it out to shareholders. If the money is paid out to shareholders as a return of capital. It’s not taxed as ordinary income. Instead, it lowers or adjusts the cost basis of the shares by the amount paid out. Eventually, the adjusted basis will be taxed as a capital gain when you sell the shares. Unless the share price drops and it becomes a capital loss.

Say you have 1,000 shares with a $20/share cost basis. You get a 1099-DIV showing a $2/share return on capital. Your new cost basis for those shares become $18 ($20 -$2). It’s fairly simple but gets complicated the more lot IDs you track and have to adjust.

One easy way to track your cost basis is to use a simple spreadsheet. It lets you know exactly where you stand before any transaction and throughout the year. When it’s time to finally do your taxes, it makes calculating cost basis that much easier.

You can download our free cost basis spreadsheet template below. It’s available in CSV format:

Just click the link, save the file, and open it in Google Sheets or Excel. Feel free to make changes, improve it, and share it.

If you don’t want to use a spreadsheet, make sure you find an online broker that tracks your cost basis for you. And if you change brokers, and transfer shares in the process, make sure to copy that cost basis information before closing your old account.

Every time you buy a stock or fund you start a paper trail that will directly impact your future taxes. But when it comes time to sell those shares, calculating cost basis and good records will decide your tax burden. The hard part is deciding which lot ID to sell.

Of course, the workaround is to keep good records going forward. The better discount brokers let you download your transaction statements complete with all your cost basis information. Keeping your own separate records is a good idea too.

Remember, the goal of investing is to get the best after-tax return over time. If your records are accurate and up to date, you only have to choose those shares with the basis and holding period that give you the best results now and in the future.